Tuesday, August 16, 2005

Love Breeds Resistance - It's In the Water

A sermon for Pentecost 14

Exodus 1:8-2:10; Romans 12:1-8

By Christian Skoorsmith

(First published on DesperatePreacher.com, August 2005)

How many of you have ever broken a rule? (show of hands)

How many of you have ever broken a law? (show of hands) Honestly? (Never broken the speed limit?)

How many of you have ever broken a rule out of principle, out of selflessness rather than selfishness – a rule that was not a good rule – or yielded to a situation in which it was better to break it than follow it? (show of hands) (Have you never let someone younger or smaller than you win a card game or a race, even though you could have?)

Look at this! Look around you! Look at the revolutionary potential we have in this room. This is great! This is why we come to church – to remind ourselves that there are values higher than our culture or government or economy or tv-commercials would have us believe, and to remind ourselves that we’re not alone in this struggle. And a Sunday every now and again we’re reminded of how inspiring and inspired these usually quiet and obedient people sitting next to you can be. Deep inside ourselves a part of us knows that oftentimes the only thing that can change a world desperately in need of being changed is the breaking of some rules – and here we have a whole room of people who join you in that awareness, and have even on occasion done it themselves. Now that’s exciting!

Of course, there’s a difference between letting a child win a game, and running afoul of your culture or your laws. No one stares or turns their heads if you don’t win a race with a five-year-old. When people start to challenge bigger problems, more deeply woven into our culture or state, things get uncomfortable.

Now, of course, some rules are good, like traffic laws, and so we follow them. (Mostly.) But if we were racing to get our sick child or parent to the hospital, well turn-signals and speed limits be damned! Some things are more important that following the rules. So laws aren’t good just because they’re laws. Just because our leaders, or our politicians, or our bosses, or our parents say something, doesn’t make it true, or right, or wise, or just. Right? (Really – am I right?) And some laws are easy to break – so I drove 66 miles-per-hour on the interstate on the way here, no big deal. But sitting in and being arrested for civil disobedience to end segregation or violence – that’s tough. A key to understanding principled rule-breaking is the motive – is it done out of selfishness or selflessness?

Let’s name some good lawbreakers? (Martin Luther King, Jr., Harriett Tubman, Eugene Debs, Henry David Thoreau, Rosa Parks, Hugh Thompson… Jesus) That’s right! Straight from the big guy himself – lawbreaking and rabble-rousing, agitation and excitation, speaking truth to power and knocking over tables in the Temple, comes very highly recommended!

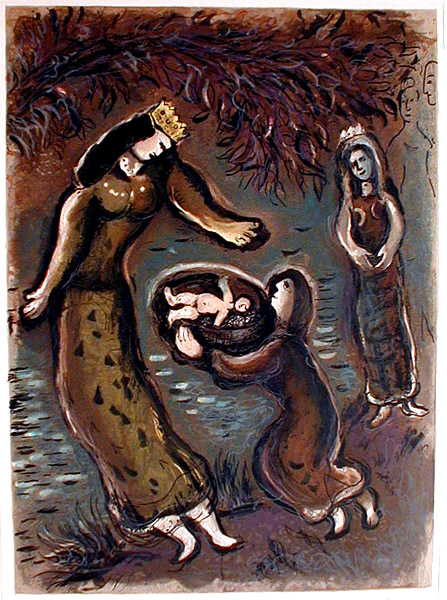

But our noble tradition of throwing mud in the eye of the rulers is much longer that just 2005 years. Today’s scripture from Exodus tells a story of some tremendously courageous and creative resistance by some very unlikely people.

How many people know who Moses was? Quite a hero – wasn’t he? (He challenged a few rules in his day, that’s for sure.) How many people know the story of his childhood? How he was born a slave and raised as a prince? Well, in that story there is this remarkable chapter that we often overlook in our eagerness to get to the action scenes. It’s worth taking a closer look at.

At this point in the Bible, where are the Hebrews at this time? Right – they’re in Egypt. What are they doing there? Right – they’re slaves, and have been for many years. Who rules over them? Right – the Pharaoh. But the old Pharaoh dies, and….

(Continue while reading from Exodus 1:8-2:10.)

(1:8) “A new king rose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph.” There’s always a new king, isn’t there? Always a new ruler – someone who wants to rule over people, influence people, command people. Say hello to the new boss, same as the old boss, right?

But this new Pharaoh doesn’t remember Joseph. Who was Joseph? He was a Hebrew who guided the earlier Pharaoh in national policy that helped save the country in spite of a seven-year-long drought and famine. So Egypt owes him and his people a debt of gratitude – the wealth and power and life-style they enjoy was created and saved by these slaves.

But this new Pharaoh doesn’t remember that. He is the Ruler. He owes nothing to no one. Everyone owes everything to him. (This is how rulers often think.) And what do rulers think about? Like every new ruler, the first thing Pharaoh thinks about is what threatens his hold on power.

(1:9) “Look,” he says, “there’re so many Israelites that they outnumber us. If these slaves ever figure out that, they could overthrow us!” Now why would he worry about being overthrown? Because the rulers aren’t treating the people under their control very well – they never do. The people are slaves – in his mind the people exist only to make him powerful, to make him rich, to make him greater than just a man, to make him more like a god. He doesn’t want to lose that.

So what is his strategy for avoiding revolution? (1:10-11) “Let us deal more harshly with them. Let’s treat them even worse – so they won’t ever dare to rebel against us!”

Now think about this for a second. This doesn’t make sense. If you want to make someone like you (you, right there in the second row there), would you start being more mean to them? No! But kings and presidents don’t care if the people they oppress like them – they only care that they won’t rebel. Fear is more compelling to kings and rulers than love. You see, this is the logic of Empire. This is the rationale of the rulers, the language of the lords, the reason of Empire.

This new king’s first concern is not helping people, not sympathizing with people, not changing the relations of production and resources and wealth and power to answer the material needs of the oppressed. No, the king’s first concern is securing power. Pharaoh’s answer to people resisting oppression – or even potentially resisting – is to oppress them more! It’s nothing new – it was the case for Pharaoh, it was the case in Jesus’ day, it was the case on American slave plantations in the 1800’s, it has been the strategy of kings and tyrants and power-holders for thousands of years and still commands the politics today! Saddam Hussein used fear to control his people. Osama bin Laden uses fear to control the Western world. Bush uses fear to control us here in the US.

But that’s not the whole story – oh no. (1:12) What is also the case is that the more this Pharaoh oppressed the Israelites, the deeper their resistance grew. As the Pharaoh worked them harder, still deeper their resentment grew. (1:13-14) The Israelites grew in size and so did the threat they posed to the empire, so Pharaoh grew to hate them even more, and he worked them even harder. And still, the spirit of those oppressed people would not break entirely.

Finally, Pharaoh went after the women – because that’s how rulers and bullies think, they always try to find the people they think are the weakest and pick on them – and Pharaoh told the midwives when they help deliver children, if it was a boy kill it, and if it was a girl let it live. (1:15-16) But this is the other thing about rulers – no matter how much they think they know who is weak and who will not resist, they don’t really know. Pharaoh didn’t know who he was picking on when he started in on these women - these Hebrew midwives don’t stand up and protest Pharaoh, but they also don’t do as he said. (1:17)

(1:19) Pharaoh brings them in and demands to know - why aren’t they killing the baby boys?! What do these poor, weak, frightened women say to this great and powerful man? Showing surprising creativity they say “the Hebrew women are too strong, and they have the babies before we can get there!” So what’s Pharaoh to do?

(1:22) He says, “throw the baby boys in the river, then! Just get rid of them!” And he probably threatened to kill the midwives, too, if they didn’t obey. (Rulers are always the ones instigating violence, you see, and always decrying it’s use by others – remember that this all started with Pharaoh not wanting the people to rise up against him, against the system, against the Establishment and the status quo. That violence would be bad. But power-holders hardly ever make the connection to the violence they initiate. The logic of Empire is twisted, indeed. But back to the story.)

Despite all this, still the Hebrew women resist! (2:2-3) They hide their babies, feed them in secret, hush them when the guards are near, smile at them and nuzzle them when they are alone. All the while, Pharaoh’s command loomed over them – throw them in the river.

Finally, when one woman could hide her son no longer, she took the Pharaoh at his word and prepared to put the child in the river – but she wasn’t going to let her baby go without some protection, and she built a small basket, an ark, if you will, and set the baby child adrift in the river. Even this last act of a mother stands in defiance of the cruelty of the Pharaoh. A tragic end to a tragic story… or is it?

Suddenly, there’s an unexpected turn of events – the baby is discovered by none other than the Pharaoh’s daughter, who takes pity on it and decides to adopt it. (2:5-6) The baby’s sister is hiding in the reeds and sees this – and then showing some quick thinking of her own, she asks Pharaoh’s daughter if she wouldn’t need a nurse for the child – meaning of course the child’s own natural mother. (2:7-10) Amazing!

And we know who this baby is, of course. When he grows up, he will lead a massive rebellion that will liberate his own people from bondage. Yet another example of how the seeds of a ruler’s undoing are nursed right in his own house. Oftentimes kings and tyrants are their own grave-diggers.

It also shows us that successful resistance movements will have a few allies in the ruling class – in this case, Pharaoh’s daughter – and that the way we will win them to our side is through their love. She saw a helpless little child adrift in the river, and raised him as her own son. She named him Moses – because, she said, the name meant “drawn from the water.”

When there’s oppression about you can’t help but respond by resisting in surprising ways – siding with those with which one isn’t supposed to side, seeing the world as the oppressed see it, loving those one isn’t supposed to love – be careful what you drink, around oppression there’s always something in the water.

Let us turn to today’s New Testament reading, Paul’s letter to the Christian in Rome, Chapter 12. (12:1-8)

(Read 12:1 again) – A living sacrifice – present your bodies – this is your spiritual worship. Listen to the language here. Living. Bodies. This is your worship. Not prayers in church. Not tithes. Not reading your bible or singing praise songs. Worship is not sacrifice at the Temple – but getting your bodies in the streets and ending injustice! If there is poverty, don’t stop at giving to the poor – end poverty! If there is illness, don’t stop at caring for one sick person – make sure everyone has health care! If there are strangers and foreigners with no place to stay, don’t stop at giving one migrant worker a ride to her job – end the economic privation and injustice that forces people to leave their homes and live in squalor in foreign countries just to earn enough to eat.

(Read 12:2) – Do not be conformed to this world, but be so moved by this world and by your vision of what it ought to be, what it could be, that you can see both how it should be and how you can make it that way, how you can bring about Zion, Heaven on Earth, the Good and Acceptable Year of the Lord.

(Read 12:3) – Do not think more highly of yourselves than you ought to think…. Ask yourselves whether you deserve more than others, or whether others in other parts of town, in other counties, in other states, in other nations, in vastly different parts of the world deserve less than you. I am truly convinced that if we are to see this Great and Acceptable Year of the Lord, we rich Americans will have to begin to give up many of our ridiculous luxuries, live more simply so that others may simply live.

Do not think more highly of yourselves…. Do we as a people, as a nation, have the authority to tell other people how they should live? What values they should have? How they should create meaning among themselves or govern themselves? These are the questions we have to ask ourselves, our culture, our government. These are the questions we have to ask as Christians, and as human beings confessing a faith in something greater than ourselves.

(Read 12:4-5) – Now this is really exciting. We don’t all have to be the same. We’re all different. But we can be united to fight for common causes. Jesus doesn’t care whether you’re a Republican or Democrat, as long as you are genuinely fighting to end poverty, end wage slavery, end exploitation, end social and economic class distinctions, end privilege and preference, and give more power to those denied power by the present way of things. Why should we do this? Why should we come together to work for these radical, progressive causes? Because we many are one body in Christ. And when we realize we are all one body in Christ, we realize we are members of one another. An injury to one, my friends, is an injury to all. If there is injustice anywhere, my brothers and sisters in Christ, it is a threat to justice everywhere.

In the words of Eugene Debs, but I can imagine it coming from the mouth of Christ: “If there is a lower class, I am in it. If there is injustice, it is done to me. If there is a criminal element, I am of it. While there is a soul in prison, I am not free.”

In Christ we are not Americans. In Christ we are not white or black. In Christ we are not English-speakers or Spanish-speakers. In Christ we are not Democrats or Republicans. In Christ, sisters and brothers, we are all people – we are Mexican and Cuban and Iraqi and Iranian and French and Afghan and Sudanese and Bosnian – we are Christian and Jew and Muslim and Sikh and Buddhist – we are rich and poor and feasting and starving – we are young and old and healthy and sick and being born and dying. We are one world, united by Christ, united by the one power we hold above all others – that of Love. And love calls not just our enemies to risk and change, it calls us too.

We all have different gifts, and live in different countries, run in different circles. Some are ministers, some teachers, some givers, some leaders, some compassionate. But we must unite, and realize the true worship of God, to borrow from the prophets, is not worship in the Temple, isn’t allegiance to the state, it is the way we live our lives, where we put our personal and communal resources – whether we sacrifice them at the altar of patriotism (which would have us believe we are not the same as other people in the world), or whether we would make them a living sacrifice.

Well, you say, that story’s all well and good – Pharaoh was obviously cruel and deserved to be resisted. Paul lived in the Roman empire, which was certainly bad news. But we don’t live under Pharaoh today. We don’t have a king. We live in a democracy! We don’t need to resist anymore. … And yet, Martin Luther King felt it necessary to resist. Rosa Parks resisted. Gandhi felt it necessary to resist – and he lived in a democracy, too. Slaves a century ago and poor people a generation ago resisted. Who can honestly say that these is no injustice, no cruelty, no inequality… even in our own land.

How many of us are willing to look at our own laws right now, our own customs here and our own military campaigns abroad, and genuinely ask if they might not serve justice – and if they don’t, commit ourselves to resisting them?

Ahh… these questions get tougher and tougher to answer. We don’t want to rock the boat, seem impolite, lose our less radical friends, perhaps go to jail or worse. So it is easier – far, far easier – to just stay home, just go to work, just vote every couple years and let the rulers decide what’s what.

But it helps to remember the Hebrew midwives under Pharaoh, and Paul in Rome.

At our best, what do we do when faced with unjust laws, untrue statements, bad values? You, me, we Christians? We resist. A tradition as old and treasured as history – resistance is a precious duty we Christians are especially beholden to. Our faith is one oftentimes of standing against our cultures, our governments, the world. Being not conformed to this world, but transforming it. Let’s not forget this. Saying no, saying this is wrong, saying I will not participate, saying I can imagine a better way of being, is a sacrament demonstrated by Jesus himself – and a longstanding demand of our faith.

It isn’t easy. Isn’t comfortable. Isn’t profitable. But, I think if we look inside ourselves we’ll all agree, that following Jesus isn’t about being comfortable, making profit, or taking the easy way. And I think we’ll also agree that we are all one body in Christ – and a body doesn’t starve one hand to feast the other, doesn’t sacrifice one limb to clothe the other in finest silk, doesn’t force one to labor harder in order to spare the other. When we realize that we are all one body, the world changes… or begins to change. Jesus didn’t transform the entire world – he started small and struggled against great earthly powers. In a lot of ways, the path of Jesus hasn’t changed all that much.

I pray we will be able to join him in the struggle, and see the liberation of all slaves, the drawing of all children out of the rivers that threaten to drown them, and do away with all pharaohs. A-men.

Labels: Sermons

Living the Kingdom

A Sermon for Pentecost 10

By [Flannel Christian]

(First Published by DesperatePreacher.com, July 2005)

We all know the story of Aladdin and his magic lamp. Remember, when he rubs it a genie comes out and offers to grant him three wishes. Through some creative wording, he manages to get a couple more, but the point is that he can’t just keep on wishing willy-nilly. He has to choose what he would most like given to him.

(To kids first, then some adults:) What would you like to wish for? What do you want most? (Take answers.) It’s funny how our answers change as we get older, or our situations change. Our priorities shift, or our means expand or shrink. Part of the puzzle is, of course, to get the most out of your wish – and so you have to imagine not only what you want most, but what you don’t think that you could get by yourself. There are times when you’d really like a drink of water, but you’re not going to waste a wish on that, because you could just walk to the sink and get yourself one, right? So what do you want most, that you don’t think you’re capable of getting yourself?

Now, of course, out of all these answers, while there’s no wrong answer, some answers are better than others, right? Some answers are selfish, others are generous; some temporary, some lasting; some specific, some general. But what were some of the best answers – and why? (Take answers.)

Today’s scripture reading tells us the story of Solomon – when God appears to him in a dream and asks Solomon to tell Him what He should give Solomon – make a wish, God is saying. Now, Solomon’s situation is a little different from ours – he’s already king, so he’s guaranteed housing and food and a retirement fund. He already has what some people would naturally ask for. But that doesn’t mean he didn’t have anything to wish for.

So God asks Solomon to make a wish, and what does Solomon wish for? (Take answers.)

That’s right! Solomon asked for an understanding mind, the ability to discern between good and evil, so he could govern the way God would want him to govern. Was that a good wish? Yes, that was a very good wish. How do we know? (all kinds of reasons) God even said so.

God said to Solomon, because you have made a good wish, and not asked for something silly like long life or riches, or something selfish and mean like the lives of your enemies, I will grant you your wish.

Oh, wouldn’t it be great if our leaders today could stop asking for more riches, if they could stop demanding the lives of their enemies? Imagine if our politicians stopped to ask for an understanding heart. What would happen to our world? Wouldn’t that be fantastic? Now, Solomon was still human, and he made some mistakes, but he started off on the right foot, with humility and a desire to seek more understanding – not coming into office thinking he knew everything already.

If only Solomon lived long enough to meet Jesus, he would have learned quite a lot about what a kingdom inspired by God would look like – and then he could have saved his wish for a new microwave or a fancy car.

You see, Jesus spent a lot of his time talking to people about what the world would be like if everyone lived the way God would want them to live. And people would all the time ask him about what the kingdom of heaven is like. Today’s Gospel reading is a series of parables – metaphors or stories – answering that very question.

In Matthew 13:31, Jesus says the kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed – the smallest of seeds that grows into a mighty… shrub. A shrub? You can imagine the crowd wondering at this one. Jesus couldn’t think of anything more mighty, more inspiring than a shrub? What about the towering cedars of Lebanon? The Temple pillars in Jerusalem? What about the unending ocean? Or a huge mountain? This is the best Jesus can think of? A shrub? The kingdom of heaven is like a… shrub.

I think Jesus was being deliberate there – he was indicting our prejudice in favor of things that are big. We “supersize” our meals, buy Hummers and ride in limousines, build bigger stadiums, build bigger churches with towering crosses on the roadside, we pump iron to make ourselves bigger. Bigger is better, our world says. And yet… Jesus says the kingdom of heaven is entirely the opposite. Small, homely, lowly, humble. Bigness isn’t all it’s cracked up to be – too big and you push away so much of the world. Don’t try to be like the towering cedars of Lebanon – be like the mustard shrub, make a place for small birds to come and nest in your branches. Be so humble that people might not even notice you – relax and be natural around you.

In the next parable, Jesus says that the kingdom of heaven is like yeast that a woman took and mixed in with a lot of bread. Now, this doesn’t seem all that shocking to us – bread-making is a fine activity. But back then, yeast was a symbol of evil influence—throughout Rabbinical writings “leaven” is a metaphor for how evil spreads among people, and you can even see that still present in Jesus’ day when Matthew a few chapters later uses it that way (16:6), Mark (8:15), Luke (12:1) and even Paul (1 Cor. 5:7-8)! It’s like me saying today that the kingdom of heaven is like the Ku Klux Klan – people must have been so startled as to wonder if Jesus was off his rocker! It doesn’t make sense!

And that’s not all – you have to remember that making bread was women’s work – in a time when women were not very highly thought of. (Not too unlike today when we think about why mothers aren’t paid for the work they do at home in raising society’s children – we don’t value their work in the same way we value “commercial” work. But that’s another sermon altogether.)

I think Jesus was being very creative by using the image of a woman working yeast into bread. First of all, Jesus is saying not everything you think is evil actually is. But more than that, the thing about yeast is it dissolves, disappears, and yet still manages to work. It works in secret, slowly, spreading itself throughout the dough and then raising the whole loaf. It sounds to me like Jesus was advocating being sneaky! Good, he seemed to say, can influence the world the same way that evil can, little by little. Also notice that the only thing smaller than a mustard seed is a spec of yeast! Here we go again – the kingdom of heaven isn’t loud or obnoxious, it isn’t big or overstated – there’s no parable of the Christian bumper-sticker, or roadside billboard. The parable is of something so small that it virtually disappears, but still manages to raise the whole.

Then we skip a few verses to the next set of parables about the kingdom of heaven, and Jesus says the kingdom of heaven is like a treasure in a field – when a man finds it, he sells everything he owns to buy that field. And the next story is of a pearl merchant who finds the one pearl that is worth more than all others, and he sells everything he has in order to buy that one pearl. Jesus is saying that the kingdom of heaven is so valuable that when someone finds it, they are ready to give up everything but not count it a sacrifice at all. Think about that! Let’s go back to Solomon for a moment – what would his kingdom have looked like if he’d taken Jesus’ words to heart?

A man who discovers the kingdom of heaven sacrifices everything without feeling like it is a sacrifice at all. What could Solomon have done that would be like this? (take answers: sell his clothing to feed the hungry, hire builders to build homes for the homeless, redistribute the land so that poor people could have farms and playgrounds, etc.) And he wouldn’t feel like that was a sacrifice at all, because he found the one thing of value above all others: the kingdom of heaven.

If only Jesus was around advise Solomon. Wise old Solomon, who for all his wisdom couldn’t have imagined what it would take to build the kingdom of heaven. “The kingdom of heaven is like a net that is thrown into the sea and caught fish of every kind.” Not just kings, or priests, or farmers, or Hebrews, or Christians, or white people, or rich people, or English-speakers, or Americans – everyone can be caught up in the kingdom of heaven. There’s no cult of purity (the way the priests of Jesus’ day would make it seem), no requisite sameness (the way the locals made it seem in villages that Jesus visited), no nationality or body or even religion that is set apart. According to Jesus, there is no “church of the perfect.”

But when all is said and done, when the nets are brought ashore, and we see who works for the lowly, the humble, the starving, the villains, the criminals, the victims, the unclean, the poor – and works to see them all cared for equally – then the fish are sorted into the good and the bad. This is the point of the story. Everyone has the chance to be caught up in the kingdom, but so many don’t, and they continue to live their selfish, individual, nationalistic, wealthy lives. Solomon wished he could know how to govern his kingdom to become the kingdom of God. But in the end, he couldn’t imagine what it would take – it would require his giving up rule, giving up wealth, giving up being separated or above anyone. If only he’d known Jesus.

But we do. We know Jesus. And we know what the kingdom looks like. We are right now caught up in the net, and can feel ourselves being pulled toward the greater good.

Will we have the courage to take that leap? It’s not something we can just wish for – there’s no magic lamp that will grant it to us. We have to truly want it, and act to bring it about. It takes work and sacrifice – but it’s worth it. Will we go down that road someday? I hope so. And I hope we’re not alone. I hope we someday give up bigness, give up riches, give up purity or separatedness, abolish poverty worldwide, and love everyone as if we were all sisters and brothers in the kingdom of heaven. For once we begin living the Kingdom life, we live in the Kingdom. Will you join me? Will our culture and nation answer this call? This is my enduring prayer.

Labels: Sermons

When Bad Things Happen to Good People

A Sermon for Pentecost 5

Genesis 21:8-21, Matthew 10:24-39

(First published by DesperatePreacher.com, May 2005)

It’s the classic problem, really: Why do bad things happen to good people?

It’s a loaded question—with hints of doubt, anger and fear—it threatens our sense of justice and of God’s goodness. It has been a question that for centuries theologians, prophets, and common everyday people like us have wrestled with. It’s not an easy question to answer; and the answer has a lot to do with how you approach the world, your relationships with other people (both loved ones and strangers far away), and how you approach your God.

Today’s scripture from Genesis tells a part of the story of Abraham—although he’s not the central figure here. The main characters are actually his wives, and to a lesser degree his sons. You see, at this point God has promised Abraham that God will raise a nation out of Abraham’s descendants. But you’ll remember that he and his wife, Sarah, couldn’t get pregnant. So Abraham took another wife, his maid-servant Hagar, and she bore him a son, Ishmael, and Abraham was happy. A little while later Sarah miraculously conceives and gives birth to Isaac. Now you can start to see the tension here.

The crisis comes when Sarah sees little Isaac playing with his elder half-brother Ishmael. Sarah becomes jealous—she was probably a little jealous before, Hagar becoming pregnant and her son being Abraham’s first-born son. But now that Sarah has her own son, things are a little different. And as much as she was concerned about the nation that would follow Abraham’s descendents, at that moment she was probably more concerned about little Isaac being as loved by Abraham as Ishmael was.

So in a terrible testament to human shortcomings, Sarah asks her husband to get rid of Hagar and Ishmael—send them away, she says. “To where?” Abraham asks. “I don’t care, just send them away.”

Understandably, Abraham is more than a little upset. He obviously cares for Hagar, and this is his son, after all. So he takes his troubles to God, and God tells Abraham not to worry about Hagar and Ishmael, and to do as Sarah says. It doesn’t make it easier for Abraham to do it, but I can imagine his seeing God’s reasoning here.

God is saying first that family is most important. In marriage, Abraham made a covenant with Sarah, and if she feels this strongly about it, for the sake of the family he should do as she wishes. It is sad and upsetting, and in a perfect world Sarah would not be so unforgiving, so unloving. But she is human, and flawed, and all too often our faults show at their worst when dealing with people closest to us.

But Abraham doesn’t send Hagar off with nothing – the next morning he burdens her down with food and water, and tearfully sends her and Ishmael off.

Hagar wanders around, hurt and lost inside herself, grieving for her home and the future of her son. And soon the food and water run out. She can’t bear to see the hunger on Ishmael’s face as he withers away. So she sets the child down under a bush, out of the sun, and goes just close enough that she can make sure that nothing happens to the child, but far enough away that she can’t watch her own child die in the desert. She put her weary head into her arms and cried. But then God enters the story a second time.

God sits down beside Hagar and says to her: “Don’t be afraid, I have heard the voice of the child. Don’t worry, he will live, and I will make a nation out of his descendents, too.” And God shows Hagar a well of water nearby, and she filled her canteen and ran back to give Ishmael a drink. He would survive.

Now, this doesn’t mean everything is alright. Hagar is still hurt, she must still find food and shelter and raise a young boy by herself. It’s not like she won the lottery and has no more cares in the world. Nothing about the situation has changed all that much, except that God has shown care for her when no one else would. But sometimes, that makes all the difference.

There’s a couple lessons to be found in this episode. Hagar learned that precious few situations are genuinely hopeless, even when things seem at their worst. She also learned that good things can come from bad. Not always, and this doesn’t make the bad good-in-disguise. Sarah’s jealousy and vindictiveness, and Abraham’s apparent unwillingness to defend Hagar against Sarah’s spite, are bad. There’s no getting around that, and let’s not confuse the issue by trying to say that because some good came from it in the end that those feelings and reactions were good to begin with. Oh no.

For however much Hagar was happy to hear that her son would survive and build a nation, too, I’m sure she would have been much happier had Sarah swallowed her pride and allowed Abraham to be a father to two sons. Would that have been better? Of course. But people don’t always make the right decisions. It doesn’t mean that everything thereafter is necessarily bad, but the ability of people to transform situations into good things doesn’t change the essential evil of those bad decisions that started us down this road.

So Hagar learned that good can come from bad, that that doesn’t mean that the bad was actually good, but that one thing God can provide is a reason to hope.

Meanwhile, Sarah is at home when she hears the news that God is out in the desert spending time with Hagar and Ishmael. That’s Abraham’s God! Why isn’t God here at our tent with us?! And it takes a while before Sarah is ready to accept her lesson: God loves and works with even those whom we hate and would cast out. Even the people we send away, or sentence to walk in the desert alone… the people we would be rid of, the people who are objects of our jealousy, our spite, our vindictiveness, our blame. Even those people, God loves and cares for. Even they deserve a home, food, water, happiness.

It is a hard pill to swallow – to see so clearly how wrongly one has acted, and how much one has hurt another person, another mother, even, just caring for her child. It is tough for us to see in people we hate the things we share in common, and our role in making them what they are. But that is the lesson God lays before us in caring for all people—our enemies, the poor, the sick, the criminal, the murderer.

In Matthew 10:29&30 we read, “Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father. And even the hairs of your head are all counted.” God cares about everything and everyone in the world – even the things that are most expendable to us, or most disgusting, or most terrifying, or most confusing, or most foreign. No matter how much we dislike or hate someone, or no matter even how little we care about someone, God is still working with them. God is still caring about them.

There’s a little comfort in there – that no matter how badly we act, no matter how cruel or spiteful we become, God will still be with that other person. We can’t act evil enough toward someone to make God not want to be with them. And inversely, despite even our worst shortfalls in being a better human, God will never give up calling us to be more loving. God will never give up asking us to risk more for love. And very rarely is a situation entirely without hope of redemption.

Why do bad things happen to good people? Sometimes, bad things just happen. Sometimes they happen as a result of things people do – intentionally or not, maliciously or not. But there shouldn’t be any surprise in that. But that’s not the end of the story. Good things happen, too. And sometimes good things happen within, or because of, or through bad things. That doesn’t mean that the bad stuff that happens isn’t bad. Oh, it is. But it does mean that something different is there. In the worst moments (as well as the best) God’s love is there – and where God is, there is yet reason to hope, yet reason to love. And that’s comforting in itself.

There is always the possibility that we can love all children as our own, love their mothers and fathers as members our own family. Nations will be born from the fruits of our actions either way, but we can choose now what our descendents will inherit from us – a legacy of jealousy and cruelty, or one of loving acceptance and nurturing. Neither one is easy. But one is the one God calls us to, and that makes all the difference.

Labels: Sermons