Monday, September 11, 2006

When Jesus Became Christian

Sermon for Day Before 9-11

This is a sermon I preached to a politically-conservative congregation on the day before "Patriot Day". Beautifully, it was a Communion service, and also included bringing an offering of food to the altar as an ongoing donation collection for a local food shelter. The Spirit was good, and worship full. What follows, of course, isn't exactly what I said - for one thing it is very long (35 minutes), and I cut out a lot the night before. But I include the entire text here. -CS

When Jesus Became Christian

By Christian Skoorsmith

At the Community of Christ, Auburn Congregation

Auburn, Washington, USA

Sept. 10, 2006

Mark 7:24-37

I have really struggled with what to say about this scripture today. First there is the scripture itself, which is a tough one, but then there is also “today” – specifically September 10th, the day before September 11th, a day of national tragedy and now on our calendars as “Patriot Day.” What do we say about this scripture and this day here, in church, in worship, in a communion service in which we rededicate ourselves to the coming kingdom of God? It’s too big a question for me alone, so I’m going to need your help. I know we don’t usually do this, but if you could, when the Spirit moves you or speaks to you or challenges you or calls to you, or even if you know what I’m talking about, just call out “A-men.” Let’s try it. “We love Jesus.” (A-men.) “We promote communities of Joy, Hope, Love and Peace.” (A-men.) “We are a prophetic people.” (A-men.) “We are called.” (A-men.) “Go Seahawks!” … Well, I thought I’d try.

Today’s scripture is a difficult one to talk about. On the one hand, you have a brave woman seeking a miracle. On the other, you have Jesus not sounding very Jesus-y. The scripture is awkward and disturbing, even more so when we begin to understand what Jesus was actually saying.

It isn’t some marginal character saying these things – it’s Jesus. And this is no modest slip of the tongue - its language is full of excess and exaggeration. Once we understand what Jesus is saying, he comes off sounding like a racist, insensitive jerk. No wonder Christians don’t like to talk about this. In fact, I bet most of us here don’t even know this story – I mean, really know this story. Even if we’ve read it before, we’ve probably seen it through our modern expectations – we expect Jesus to be the model of love and tolerance.

But, if we’re going to follow Jesus – the real Jesus, and not some picture-perfect story-book version of Jesus – then we have to know this story. So here it is.

In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus spends the first part of chapter 7 talking about cleanliness laws – what’s clean food to eat and what’s unclean. He lambastes the Pharisees for assuming human conventions are divine laws or nature, for “teaching human precepts as doctrine.” (v. 7) We all know what he’s talking about here, right? We’ve all seen it at one time or another, someone saying that their prejudices or customs or opinions are actually God’s Will. (A-men?) Jesus was calling them on this. And pretty much turning the law upside-down, Jesus says it isn’t what goes into a person that defiles them, but what comes out of them – not what we eat, but what we say and do, where we put our money, what we support or resist, what we teach our children, and at the extreme, where we give our lives. This might be foreshadowing for our particular scripture today.

After dealing with the Pharisees, Mark tells us, Jesus escapes from the region and arrives at the city of Tyre. The way Mark sets it up, Jesus was tired of being hounded by hypocrites and prejudiced people, and just wanted a break. Now Tyre was a racially, ethnically, economically and politically diverse city. There are Arabs, Greeks, Syrians, Romans, and Persians, as well as Jews. There’s rich people and poor people, powerful people, soldiers, regular people, disenfranchised people. And perhaps Jesus is hoping he can just blend in, get away from the crowds. Who can blame him? He’s hoping he won’t be bothered. But he’s wrong, and a woman comes asking for a miracle.

Isn’t that always the way? Whenever we get tired of dealing with people’s prejudices or short-sightedness, and all we want is a break, that’s when God still bothers us, always asking for a miracle. (A-men?) (God also bothered Jesus at Gethsemane, when he was saying “just give me a break, here!”)

(Remove this paragraph?) This little episode we’re about to discuss is at a turning-point of the gospel. You probably haven’t noticed it, but in Mark’s Gospel up until this point Jesus has stuck pretty much to the Jews – Jesus is, after all, a Jew, talking to Jews about how to be a good Jew. After this point, however, the gospel looks very different. The entire gospel of Mark, indeed the whole history of Christianity, pivots on two verses; the gospel radically changes and with it changes the kind of disciples Jesus followers would find themselves called to be; one of the defining moments of our religion and our understanding of God hinges between two verses, and they’re in today’s scripture reading. Despite how important they are, oftentimes we overlook them, because we’re reading the Bible backwards – we already know how it ends, and so we read it with 2000 years of tradition layered on top of it. We think we know what it means already. But, if we want to know what it meant to Mark and his first-century audience, we have to look at it more closely.

Jesus is hiding out, tired from the crowds who always want more; he’s still steaming at the Pharisee hypocrisy; and probably more than a little frustrated with his own disciples who don’t even seem to get! All he wants is a break. And here comes this lady begging for a miracle.

Is that all these people want? Miracles? No one believes unless they can see! Unless they get something out of it! So Jesus just ignores her.

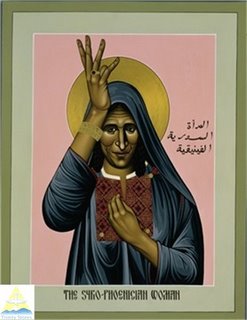

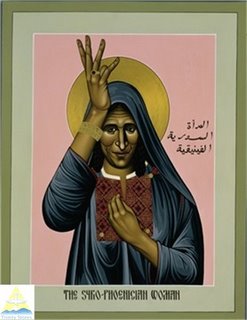

And not only is this lady not taking the hint and getting lost, she’s also clearly not welcome there. You see, she’s a Gentile. She’s not Jewish. The gospel of Mark goes to some length to impress upon the reader how foreign she is – “she’s really not one of us”, Mark seems to be saying. “She’s Syro-phoenician.” Mark rarely mentions people’s nationality or ethnicity, so when he does, it’s a big deal. Matthew, when using Mark’s gospel a decade or two later as notes for his own gospel, realized this and drove the point home by calling her a “Canaanite” woman – even though there hadn’t been any “Canaanites” for hundreds of years! The gospel writers are trying to make a point here, and the point is she was really different. And in the Jewish world of laws regarding what one could or couldn’t do, could or couldn’t eat, who you could or couldn’t talk to, “different” was very, very bad.

This lady wasn’t welcome. First of all, she shouldn’t even be in this part of town. Secondly, she shouldn’t enter a Jewish home because that will defile the whole building. Next, she can’t even hope to talk to Jesus because (a) she’s a woman and women didn’t just go up and talk to men, and (b) she’s a Gentile! That’s like a double-whammy for even just talking to him! Jesus is probably disgusted that some filthy Gentile is even addressing him, let alone wanting him to answer her. And then, if he hears her, she’s asking for a miraculous healing of her daughter! Another person who just wants a favor from Jesus! And she just won’t go away. The neighbors tell her. The women of the house tell her. The disciples tell her to go away, and she just keeps asking Jesus. Finally, Jesus is just fed up! He doesn’t even look at her, but answers to the crowd that is starting to gather: “Let the children be fed first, for it isn’t fair to take the children’s food and throw it away to the dogs.” (Gasp! Pause.)

Well, ok, that doesn’t sound all that bad to us – but you have to hear with the ears of a first-century Jew and Palestinian Gentile, and all of a sudden there’s a force there that we didn’t hear.

“Dogs” was a common Hebrew pejorative that referred to pagans generally (1 Sam 17:43; 2 Kings 8:13), but by the first-century it came to apply particularly to Greek-influenced people in Palestine particularly because they let their dogs in their houses, which the Jews thought was filthy. So this is, really, a first-century racial epithet. It’s a bad word. It is like Jesus calling a black person the “n-word,” or a Vietnamese person a “gook,” or a Japanese person a “nip,” or a German a “kraut,” or a white person a “cracker,” or a gay person a “fag,” or an Arab a “towel-head.” I don’t like saying these words, especially in house such as this that demands both dignity and honesty – but we have to be honest, and these are the 20th century equivalents of what Jesus said. You should be offended by this, by these words and by the idea of Jesus saying them; you should cringe, because that’s what Mark was saying here. Jesus was at his breaking point, and tired of people telling him what to do. And it was at this moment, in a fit of anger and short-sightedness, that Jesus snapped.

Who among us hasn’t said something hurtful or spiteful in a rage of anger and frustration? Who among us can’t sympathize with Jesus’ predicament? It doesn’t mean Jesus was right to blow up and sink to that kind of language, but it can help us appreciate the humanness of Jesus. (A-men?)

But there’s more in this sentence than just that racial insult. The scripture reads: “let the children be fed” – which to our ears sounds kind of nice. But the word translated here as “children,” as it is often used in Greek, the language Mark was written in, could also mean “disciples” as it does elsewhere in the New Testament. Depending on the interpretation, Mark could have Jesus limiting the gospel just to his circle of immediate disciples. “Let only the disciples be fed,” he could be saying.

And the word translated as “fed”, chortazo, means something more along the lines of gorging yourself, eating until you’re sick, a sort of verb you only use at Thanksgiving. So it’s not as if Jesus is saying the disciples or chosen ones should get first pickings – they should absolute satiate themselves before letting one little crumb go to those unworthy other people. My point is: this is not the language of moderation here, folks. Jesus’ outburst shows all kinds of excessive language. Mark is really trying to shock the reader. You really can see the contours of someone losing their temper.

But this is story-telling, too – Mark is telling this story for a reason – so there is also a symbolic layer of meaning here. Why is Mark including this in his gospel? What is he trying to say here? In the world of Jewish Wisdom literature (like the books of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes), of which Jesus showed himself both knowledgeable and fond, and even elsewhere in the gospel, eating bread was symbolic of understanding (6:52; 8:18-21). (A more modern metaphor for understanding is seeing – “I see that.”) (Knowing this puts another spin on the Lord’s Supper, communion and potlucks – A-men?)

Food and money are both such great symbols for the gospel writers because they actually embody what they are symbolizing – so they are both real and symbolic of their own reality at the same time. With whom you share your bread or money actually means something more than just sharing food or money, right? It establishes or nurtures or transforms a relationship, a connection or separation. No wonder the gospel writers used these two images so often! Mark has Jesus not just making a statement about that one night, but about who is worthy of hearing the message of Jesus, of being part of the community of Christ, who has a right to be treated as fully human. And it is clear that Jesus will have none of this pagan-dog lady, insulting him with her mere presence.

But just when we see Jesus sink to unimaginable depths, and we start to wonder what kind of person we are lifting up as our revelation of God, something happens. This woman, who has been verbally abused, berated, denied and shunned, and who is now insulted in the most offensive way by the very person she believed could heal her daughter… she lifts up her head and answers the venom of Jesus with a surprisingly witty and incisive observation: “even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from the table of children.” She is calling Jesus out for what he said – and I don’t mean the racist remark, I mean what Jesus had spent the day teaching about.

Remember, Jesus had just spent the day telling the Pharisees that their cleanliness laws actually distracted them from the real work of God. These human prejudices of who is worthy and unworthy people lied to them and made them believe some people are better than others, or are different in the eyes of God. Jesus was saying that those divisions are created by humans, and that God’s love and compassion and power reach beyond them.

This Syro-phoenician woman was saying that even though the Gentiles are “unclean” because they live with their dogs, the Gentiles treat even their dogs with a modicum of respect. The Gentiles, in fact, treat their dogs better than Jesus was treating her. The accusations Jesus was leveling against the Pharisees earlier in the day were now being turned on him. Jesus was the hypocrite.

Something important is happening here. It is what our theme lifts up today: the Syro-Phoenician woman spoke up… she answered prejudice and violence with truth and compassion, she stood up to ridicule in order to compel the people around her to see the light. She spoke up, when she was probably very frightened to do so. This unnamed foreign woman, out of all the disciples and friends surrounding Jesus, was the only one who actually understood Jesus. She had, in a way, already tasted the bread of understanding that Jesus held out for his disciples. Our theme would have us see this woman as the hero of the story – which is great, but the story doesn’t end there.

Imagine the scene – everyone knows Jesus was being a jerk, but this lady called him on it. How would he react? Would he curse her? Send her away? Attack her? No. Jesus hears her, listens to her, and he realizes that his world in that moment is changing. She’s right, he thinks. God’s love is for everyone. God’s compassion and concern reaches beyond my social group, my religion, my “people,” my country. I say love your enemies, but have I changed my customs, my habits, my lifestyle or my politics to reflect that belief? I say bless those who curse you, but have I changed what I say and do to be in line with that? I say pray for those who mistreat you, but here am I mistreating someone!

In my opinion, there are two heroes in this story. First is the woman who spoke up and pointed out hypocrisy. But there’s also Jesus, who was willing to recognize his own short-sightedness, his own discrimination and prejudice; he was willing to measure his own behavior and presumptions against the word of God; he was willing to confront how wrong he’d been about what he thought God’s Will was, and was willing to change himself in response to that new revelation, even though changing yourself means risking some scary things like ridicule and having to love your enemies.

I’m sure he couldn’t believe that he had been so blind that whole time. But now he could see. Jesus was being converted. He was no longer just a Jew concerned only with speaking to and protecting his own people – he was a person concerned with all humanity. The irony here is that it was a gentile woman that converted Jesus to Christianity, and not the other way around.

Jesus is so stunned at this point, having to rethink everything he’s been saying and doing, that all he can think to do in response is thank this woman for her honesty and forthrightness, and the gospel writer emphasizes this with the healing of her daughter. He doesn’t say, “you’re faith has made your daughter whole,” but that might be implied here.

I’m not sure, but I bet it is at this point that Jesus began to emphasize the “repentance” part of the kingdom of God. We don’t know what word Jesus actually used in Aramaic, but the Greek word that the Gospel writers used, that we translate as “repentance”, is “metanoia.” “Meta” meaning to change (like metamorphosis and metabolism), and “noia” meaning way of knowing or perceiving. Literally, repentance is “changing your mind” or “changing the way you perceive the world”, “changing the way you think.”

Jesus was used to thinking in terms of good people and bad people, clean and unclean, worthy and unworthy, those on “our side” and those on “the other side”. And up to this point in the gospel he may have only been interested in moving those boundaries around, not necessarily in doing away with those boundaries altogether. Jesus was, really, a lot like you and me – at times not the best people we could be, willing to like some people more than others, more willing to help some people or cross some boundaries for some people and not so willing for others, more willing to forgive and work toward reconciliation with some people and not with others, more willing to understand where certain people are coming from and not willing to make that leap for others, more willing to share our table or other resources with certain people while not sharing them with others. (A-men?) Like Jesus did, we make judgments about people, and oftentimes our judgments end up looking a lot like the power structures we participate in, or benefit from, or are subject to, whether that be our culture, our nation, or sometimes our faith.

Even if we don’t like seeing it so plainly acted out, as it is in this story, we should be able to sympathize with Jesus’ feelings. After all, we’re certainly no better than Jesus, and probably we’re a lot worse. Jesus came face to face with the difference between being Christian and being a subject or citizen of some earthly power.

Jesus realized that responding to the gospel, in effect being a Christian, demands some very counter-cultural thought, demands seeing the world not as the Powers want us to see it, as the political governors or religious fundamentalists see it; but to see the world as God sees it – as fallen all over the place (including you and me) but none of it beyond redemption or unworthy of care (even those whom “The World” tells us to despise, like “terrorists” for example).

The government and Fox News and televangelists want us to fear and react out of desperation or vengeance – they want us to see people as fundamentally foreign and threatening. Jesus had to contend with the voices of Caesar and his cultural prejudices in his own head and heart – even while at the same time he was mouthing the words, saying the prayers, spreading the teachings of the gospel. Jesus struggled to meet the demands of the gospel in the face of his nation and politics and culture. And we Christians, followers of Jesus, inherit that struggle – we are set against the world, like resident-aliens or strangers in a strange land.

We struggle against Caesar and prejudice in our own hearts and minds. We struggle against the propaganda of the nation, against militarism that says violence is really the only solution to some problems, against an economic mindset that says to consume more is the way to happiness and security, against a culture in which we always have to be #1 or we’re nobody. As Christians, we hold different values. Instead of nationalist identifications that separate people along artificial geographic lines, we see all people as children of God and united in Christ’s love for them. Instead of violence, we see Love as the real solution to problems – without being pollyanish and thinking that love is easy or quick, we all know love is tough sometimes and a long-term commitment. Instead of capitalism, a system built on the exploitation of workers in our own country and around the globe, a system that believes there is a scarcity of resources and we better get ours first, we Christians believe that there is an abundance for everyone, and that if everyone shares there will always be enough – remember the loaves and fishes miracle, and the miracle every Sunday there is a potluck: everyone eats their fill and goes home with more than they came with. Instead of a world of competition against others, we Christians join with others, in prayer, in work, in offering help, in changing our world. We’re in it together, all members of one body. These are bold claims that fly in the face of the Powers That Be. And I bet even right now there are voices in your head and heart that are telling you not to agree too much. Little tentacles of the World making sure your Christian sentiments aren’t taken too seriously. Am I right? I know I feel them. I can hear those voices right now.

As followers of Jesus, we inherit that same frightening, compelling challenge that faced Jesus. But we also inherit the confidence of victory. It isn’t a victory the way the World thinks of victory – not over kingdoms or regimes, we won’t invade a country or storm the White House. Our God is the crucified God, the despised and hated God, the small and humble but very personally interested God. Jesus had no interest in the World’s kind of victory. Our victory is victory as Jesus knew victory – overcoming inside himself those voices of The World, so that he was no longer the subject of a worldly power, but of a power beyond the world, beyond the halls of power.

Brothers and sisters, how wonderful that today we take part in the sacrament of Communion, a sacrament with which we declare and recommit ourselves to citizenship in the kingdom of God, first and foremost. In Christ there is no Jew or Greek, no American or Iraqi, no terrorist or freedom fighter. We participate in a sharing of food – symbolically, a sharing of power and faith, with anyone who will join us at the table, and holding open a space even for our enemies. How perfect that this difficult scripture that speaks of the sharing of bread as a moment of transformation and opening of hearts, of understanding, is our scripture for today. This turning of hearts, this listening to the gospel, this metanoia, this turning our backs on the values of the World, is no less difficult for us than it was for Jesus. But there is a promise here. Remember that the Syro-phoenician woman had come pleading for her daughter, and as a result of this metanoia, her child was healed. There is a promise that for those of us bold enough to really listen, to take into our deepest hearts the gospel message, there is a healing waiting for us too, and not coincidentally, a healing directed primarily at our children.

The Syro-phoenician woman’s faith converted Jesus, and saved the gospel from being small-minded. But it was Jesus’ willingness to be converted, to measure himself against the gospel, that was also necessary for conversion. I wonder if the gospel writer is hoping we’ll be converted as well.

I have to admit that I find it somewhat comforting that early on even Jesus still had room for improvement early on. I can more easily forgive my own sillinesses and faults. And it is encouraging to think that real change is possible. There are moments when God takes our hearts and prejudices and has to break them in order to transform us, to get us to see things newly. When we remember to love our enemies, and bless those who curse us, and give solace to those who would use us, to minister and reach out to those who target us, that is when the gospel lives in us.

And this afternoon and tomorrow, when we are bombarded with flag-waving, speeches and television exposes, when the news and remembrances and emails start circulating, meant to whip us up into a frenzy of patriotic fear and prejudice, especially then we need to remember who we are. We are no longer captive to the world’s notions of enemies and revenge. We have been set free. We live for something more. For us Christians it’s not the American Way – it’s the Jesus way, and it is narrow and difficult.

Like Jesus, we must be converted again and again. We must struggle to become Christian. But like Jesus, the Syro-phoenician woman and her daughter, there is the promise of transformation and redemption. There is understanding waiting for us in the bread. Eat in remembrance of him.

And this afternoon and tomorrow, when we are bombarded with flag-waving, speeches and television exposes, when the news and remembrances and emails start circulating, meant to whip us up into a frenzy of patriotic fear and prejudice, especially then we need to remember who we are. We are no longer captive to the world’s notions of enemies and revenge. We have been set free. We live for something more. For us Christians it’s not the American Way – it’s the Jesus way, and it is narrow and difficult.

This is a sermon I preached to a politically-conservative congregation on the day before "Patriot Day". Beautifully, it was a Communion service, and also included bringing an offering of food to the altar as an ongoing donation collection for a local food shelter. The Spirit was good, and worship full. What follows, of course, isn't exactly what I said - for one thing it is very long (35 minutes), and I cut out a lot the night before. But I include the entire text here. -CS

By Christian Skoorsmith

At the Community of Christ, Auburn Congregation

Auburn, Washington, USA

Sept. 10, 2006

Mark 7:24-37

I have really struggled with what to say about this scripture today. First there is the scripture itself, which is a tough one, but then there is also “today” – specifically September 10th, the day before September 11th, a day of national tragedy and now on our calendars as “Patriot Day.” What do we say about this scripture and this day here, in church, in worship, in a communion service in which we rededicate ourselves to the coming kingdom of God? It’s too big a question for me alone, so I’m going to need your help. I know we don’t usually do this, but if you could, when the Spirit moves you or speaks to you or challenges you or calls to you, or even if you know what I’m talking about, just call out “A-men.” Let’s try it. “We love Jesus.” (A-men.) “We promote communities of Joy, Hope, Love and Peace.” (A-men.) “We are a prophetic people.” (A-men.) “We are called.” (A-men.) “Go Seahawks!” … Well, I thought I’d try.

Today’s scripture is a difficult one to talk about. On the one hand, you have a brave woman seeking a miracle. On the other, you have Jesus not sounding very Jesus-y. The scripture is awkward and disturbing, even more so when we begin to understand what Jesus was actually saying.

It isn’t some marginal character saying these things – it’s Jesus. And this is no modest slip of the tongue - its language is full of excess and exaggeration. Once we understand what Jesus is saying, he comes off sounding like a racist, insensitive jerk. No wonder Christians don’t like to talk about this. In fact, I bet most of us here don’t even know this story – I mean, really know this story. Even if we’ve read it before, we’ve probably seen it through our modern expectations – we expect Jesus to be the model of love and tolerance.

But, if we’re going to follow Jesus – the real Jesus, and not some picture-perfect story-book version of Jesus – then we have to know this story. So here it is.

In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus spends the first part of chapter 7 talking about cleanliness laws – what’s clean food to eat and what’s unclean. He lambastes the Pharisees for assuming human conventions are divine laws or nature, for “teaching human precepts as doctrine.” (v. 7) We all know what he’s talking about here, right? We’ve all seen it at one time or another, someone saying that their prejudices or customs or opinions are actually God’s Will. (A-men?) Jesus was calling them on this. And pretty much turning the law upside-down, Jesus says it isn’t what goes into a person that defiles them, but what comes out of them – not what we eat, but what we say and do, where we put our money, what we support or resist, what we teach our children, and at the extreme, where we give our lives. This might be foreshadowing for our particular scripture today.

After dealing with the Pharisees, Mark tells us, Jesus escapes from the region and arrives at the city of Tyre. The way Mark sets it up, Jesus was tired of being hounded by hypocrites and prejudiced people, and just wanted a break. Now Tyre was a racially, ethnically, economically and politically diverse city. There are Arabs, Greeks, Syrians, Romans, and Persians, as well as Jews. There’s rich people and poor people, powerful people, soldiers, regular people, disenfranchised people. And perhaps Jesus is hoping he can just blend in, get away from the crowds. Who can blame him? He’s hoping he won’t be bothered. But he’s wrong, and a woman comes asking for a miracle.

Isn’t that always the way? Whenever we get tired of dealing with people’s prejudices or short-sightedness, and all we want is a break, that’s when God still bothers us, always asking for a miracle. (A-men?) (God also bothered Jesus at Gethsemane, when he was saying “just give me a break, here!”)

(Remove this paragraph?) This little episode we’re about to discuss is at a turning-point of the gospel. You probably haven’t noticed it, but in Mark’s Gospel up until this point Jesus has stuck pretty much to the Jews – Jesus is, after all, a Jew, talking to Jews about how to be a good Jew. After this point, however, the gospel looks very different. The entire gospel of Mark, indeed the whole history of Christianity, pivots on two verses; the gospel radically changes and with it changes the kind of disciples Jesus followers would find themselves called to be; one of the defining moments of our religion and our understanding of God hinges between two verses, and they’re in today’s scripture reading. Despite how important they are, oftentimes we overlook them, because we’re reading the Bible backwards – we already know how it ends, and so we read it with 2000 years of tradition layered on top of it. We think we know what it means already. But, if we want to know what it meant to Mark and his first-century audience, we have to look at it more closely.

Jesus is hiding out, tired from the crowds who always want more; he’s still steaming at the Pharisee hypocrisy; and probably more than a little frustrated with his own disciples who don’t even seem to get! All he wants is a break. And here comes this lady begging for a miracle.

Is that all these people want? Miracles? No one believes unless they can see! Unless they get something out of it! So Jesus just ignores her.

And not only is this lady not taking the hint and getting lost, she’s also clearly not welcome there. You see, she’s a Gentile. She’s not Jewish. The gospel of Mark goes to some length to impress upon the reader how foreign she is – “she’s really not one of us”, Mark seems to be saying. “She’s Syro-phoenician.” Mark rarely mentions people’s nationality or ethnicity, so when he does, it’s a big deal. Matthew, when using Mark’s gospel a decade or two later as notes for his own gospel, realized this and drove the point home by calling her a “Canaanite” woman – even though there hadn’t been any “Canaanites” for hundreds of years! The gospel writers are trying to make a point here, and the point is she was really different. And in the Jewish world of laws regarding what one could or couldn’t do, could or couldn’t eat, who you could or couldn’t talk to, “different” was very, very bad.

This lady wasn’t welcome. First of all, she shouldn’t even be in this part of town. Secondly, she shouldn’t enter a Jewish home because that will defile the whole building. Next, she can’t even hope to talk to Jesus because (a) she’s a woman and women didn’t just go up and talk to men, and (b) she’s a Gentile! That’s like a double-whammy for even just talking to him! Jesus is probably disgusted that some filthy Gentile is even addressing him, let alone wanting him to answer her. And then, if he hears her, she’s asking for a miraculous healing of her daughter! Another person who just wants a favor from Jesus! And she just won’t go away. The neighbors tell her. The women of the house tell her. The disciples tell her to go away, and she just keeps asking Jesus. Finally, Jesus is just fed up! He doesn’t even look at her, but answers to the crowd that is starting to gather: “Let the children be fed first, for it isn’t fair to take the children’s food and throw it away to the dogs.” (Gasp! Pause.)

Well, ok, that doesn’t sound all that bad to us – but you have to hear with the ears of a first-century Jew and Palestinian Gentile, and all of a sudden there’s a force there that we didn’t hear.

“Dogs” was a common Hebrew pejorative that referred to pagans generally (1 Sam 17:43; 2 Kings 8:13), but by the first-century it came to apply particularly to Greek-influenced people in Palestine particularly because they let their dogs in their houses, which the Jews thought was filthy. So this is, really, a first-century racial epithet. It’s a bad word. It is like Jesus calling a black person the “n-word,” or a Vietnamese person a “gook,” or a Japanese person a “nip,” or a German a “kraut,” or a white person a “cracker,” or a gay person a “fag,” or an Arab a “towel-head.” I don’t like saying these words, especially in house such as this that demands both dignity and honesty – but we have to be honest, and these are the 20th century equivalents of what Jesus said. You should be offended by this, by these words and by the idea of Jesus saying them; you should cringe, because that’s what Mark was saying here. Jesus was at his breaking point, and tired of people telling him what to do. And it was at this moment, in a fit of anger and short-sightedness, that Jesus snapped.

Who among us hasn’t said something hurtful or spiteful in a rage of anger and frustration? Who among us can’t sympathize with Jesus’ predicament? It doesn’t mean Jesus was right to blow up and sink to that kind of language, but it can help us appreciate the humanness of Jesus. (A-men?)

But there’s more in this sentence than just that racial insult. The scripture reads: “let the children be fed” – which to our ears sounds kind of nice. But the word translated here as “children,” as it is often used in Greek, the language Mark was written in, could also mean “disciples” as it does elsewhere in the New Testament. Depending on the interpretation, Mark could have Jesus limiting the gospel just to his circle of immediate disciples. “Let only the disciples be fed,” he could be saying.

And the word translated as “fed”, chortazo, means something more along the lines of gorging yourself, eating until you’re sick, a sort of verb you only use at Thanksgiving. So it’s not as if Jesus is saying the disciples or chosen ones should get first pickings – they should absolute satiate themselves before letting one little crumb go to those unworthy other people. My point is: this is not the language of moderation here, folks. Jesus’ outburst shows all kinds of excessive language. Mark is really trying to shock the reader. You really can see the contours of someone losing their temper.

But this is story-telling, too – Mark is telling this story for a reason – so there is also a symbolic layer of meaning here. Why is Mark including this in his gospel? What is he trying to say here? In the world of Jewish Wisdom literature (like the books of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes), of which Jesus showed himself both knowledgeable and fond, and even elsewhere in the gospel, eating bread was symbolic of understanding (6:52; 8:18-21). (A more modern metaphor for understanding is seeing – “I see that.”) (Knowing this puts another spin on the Lord’s Supper, communion and potlucks – A-men?)

Food and money are both such great symbols for the gospel writers because they actually embody what they are symbolizing – so they are both real and symbolic of their own reality at the same time. With whom you share your bread or money actually means something more than just sharing food or money, right? It establishes or nurtures or transforms a relationship, a connection or separation. No wonder the gospel writers used these two images so often! Mark has Jesus not just making a statement about that one night, but about who is worthy of hearing the message of Jesus, of being part of the community of Christ, who has a right to be treated as fully human. And it is clear that Jesus will have none of this pagan-dog lady, insulting him with her mere presence.

But just when we see Jesus sink to unimaginable depths, and we start to wonder what kind of person we are lifting up as our revelation of God, something happens. This woman, who has been verbally abused, berated, denied and shunned, and who is now insulted in the most offensive way by the very person she believed could heal her daughter… she lifts up her head and answers the venom of Jesus with a surprisingly witty and incisive observation: “even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from the table of children.” She is calling Jesus out for what he said – and I don’t mean the racist remark, I mean what Jesus had spent the day teaching about.

Remember, Jesus had just spent the day telling the Pharisees that their cleanliness laws actually distracted them from the real work of God. These human prejudices of who is worthy and unworthy people lied to them and made them believe some people are better than others, or are different in the eyes of God. Jesus was saying that those divisions are created by humans, and that God’s love and compassion and power reach beyond them.

This Syro-phoenician woman was saying that even though the Gentiles are “unclean” because they live with their dogs, the Gentiles treat even their dogs with a modicum of respect. The Gentiles, in fact, treat their dogs better than Jesus was treating her. The accusations Jesus was leveling against the Pharisees earlier in the day were now being turned on him. Jesus was the hypocrite.

Something important is happening here. It is what our theme lifts up today: the Syro-Phoenician woman spoke up… she answered prejudice and violence with truth and compassion, she stood up to ridicule in order to compel the people around her to see the light. She spoke up, when she was probably very frightened to do so. This unnamed foreign woman, out of all the disciples and friends surrounding Jesus, was the only one who actually understood Jesus. She had, in a way, already tasted the bread of understanding that Jesus held out for his disciples. Our theme would have us see this woman as the hero of the story – which is great, but the story doesn’t end there.

Imagine the scene – everyone knows Jesus was being a jerk, but this lady called him on it. How would he react? Would he curse her? Send her away? Attack her? No. Jesus hears her, listens to her, and he realizes that his world in that moment is changing. She’s right, he thinks. God’s love is for everyone. God’s compassion and concern reaches beyond my social group, my religion, my “people,” my country. I say love your enemies, but have I changed my customs, my habits, my lifestyle or my politics to reflect that belief? I say bless those who curse you, but have I changed what I say and do to be in line with that? I say pray for those who mistreat you, but here am I mistreating someone!

In my opinion, there are two heroes in this story. First is the woman who spoke up and pointed out hypocrisy. But there’s also Jesus, who was willing to recognize his own short-sightedness, his own discrimination and prejudice; he was willing to measure his own behavior and presumptions against the word of God; he was willing to confront how wrong he’d been about what he thought God’s Will was, and was willing to change himself in response to that new revelation, even though changing yourself means risking some scary things like ridicule and having to love your enemies.

I’m sure he couldn’t believe that he had been so blind that whole time. But now he could see. Jesus was being converted. He was no longer just a Jew concerned only with speaking to and protecting his own people – he was a person concerned with all humanity. The irony here is that it was a gentile woman that converted Jesus to Christianity, and not the other way around.

Jesus is so stunned at this point, having to rethink everything he’s been saying and doing, that all he can think to do in response is thank this woman for her honesty and forthrightness, and the gospel writer emphasizes this with the healing of her daughter. He doesn’t say, “you’re faith has made your daughter whole,” but that might be implied here.

I’m not sure, but I bet it is at this point that Jesus began to emphasize the “repentance” part of the kingdom of God. We don’t know what word Jesus actually used in Aramaic, but the Greek word that the Gospel writers used, that we translate as “repentance”, is “metanoia.” “Meta” meaning to change (like metamorphosis and metabolism), and “noia” meaning way of knowing or perceiving. Literally, repentance is “changing your mind” or “changing the way you perceive the world”, “changing the way you think.”

Jesus was used to thinking in terms of good people and bad people, clean and unclean, worthy and unworthy, those on “our side” and those on “the other side”. And up to this point in the gospel he may have only been interested in moving those boundaries around, not necessarily in doing away with those boundaries altogether. Jesus was, really, a lot like you and me – at times not the best people we could be, willing to like some people more than others, more willing to help some people or cross some boundaries for some people and not so willing for others, more willing to forgive and work toward reconciliation with some people and not with others, more willing to understand where certain people are coming from and not willing to make that leap for others, more willing to share our table or other resources with certain people while not sharing them with others. (A-men?) Like Jesus did, we make judgments about people, and oftentimes our judgments end up looking a lot like the power structures we participate in, or benefit from, or are subject to, whether that be our culture, our nation, or sometimes our faith.

Even if we don’t like seeing it so plainly acted out, as it is in this story, we should be able to sympathize with Jesus’ feelings. After all, we’re certainly no better than Jesus, and probably we’re a lot worse. Jesus came face to face with the difference between being Christian and being a subject or citizen of some earthly power.

Jesus realized that responding to the gospel, in effect being a Christian, demands some very counter-cultural thought, demands seeing the world not as the Powers want us to see it, as the political governors or religious fundamentalists see it; but to see the world as God sees it – as fallen all over the place (including you and me) but none of it beyond redemption or unworthy of care (even those whom “The World” tells us to despise, like “terrorists” for example).

The government and Fox News and televangelists want us to fear and react out of desperation or vengeance – they want us to see people as fundamentally foreign and threatening. Jesus had to contend with the voices of Caesar and his cultural prejudices in his own head and heart – even while at the same time he was mouthing the words, saying the prayers, spreading the teachings of the gospel. Jesus struggled to meet the demands of the gospel in the face of his nation and politics and culture. And we Christians, followers of Jesus, inherit that struggle – we are set against the world, like resident-aliens or strangers in a strange land.

We struggle against Caesar and prejudice in our own hearts and minds. We struggle against the propaganda of the nation, against militarism that says violence is really the only solution to some problems, against an economic mindset that says to consume more is the way to happiness and security, against a culture in which we always have to be #1 or we’re nobody. As Christians, we hold different values. Instead of nationalist identifications that separate people along artificial geographic lines, we see all people as children of God and united in Christ’s love for them. Instead of violence, we see Love as the real solution to problems – without being pollyanish and thinking that love is easy or quick, we all know love is tough sometimes and a long-term commitment. Instead of capitalism, a system built on the exploitation of workers in our own country and around the globe, a system that believes there is a scarcity of resources and we better get ours first, we Christians believe that there is an abundance for everyone, and that if everyone shares there will always be enough – remember the loaves and fishes miracle, and the miracle every Sunday there is a potluck: everyone eats their fill and goes home with more than they came with. Instead of a world of competition against others, we Christians join with others, in prayer, in work, in offering help, in changing our world. We’re in it together, all members of one body. These are bold claims that fly in the face of the Powers That Be. And I bet even right now there are voices in your head and heart that are telling you not to agree too much. Little tentacles of the World making sure your Christian sentiments aren’t taken too seriously. Am I right? I know I feel them. I can hear those voices right now.

As followers of Jesus, we inherit that same frightening, compelling challenge that faced Jesus. But we also inherit the confidence of victory. It isn’t a victory the way the World thinks of victory – not over kingdoms or regimes, we won’t invade a country or storm the White House. Our God is the crucified God, the despised and hated God, the small and humble but very personally interested God. Jesus had no interest in the World’s kind of victory. Our victory is victory as Jesus knew victory – overcoming inside himself those voices of The World, so that he was no longer the subject of a worldly power, but of a power beyond the world, beyond the halls of power.

Brothers and sisters, how wonderful that today we take part in the sacrament of Communion, a sacrament with which we declare and recommit ourselves to citizenship in the kingdom of God, first and foremost. In Christ there is no Jew or Greek, no American or Iraqi, no terrorist or freedom fighter. We participate in a sharing of food – symbolically, a sharing of power and faith, with anyone who will join us at the table, and holding open a space even for our enemies. How perfect that this difficult scripture that speaks of the sharing of bread as a moment of transformation and opening of hearts, of understanding, is our scripture for today. This turning of hearts, this listening to the gospel, this metanoia, this turning our backs on the values of the World, is no less difficult for us than it was for Jesus. But there is a promise here. Remember that the Syro-phoenician woman had come pleading for her daughter, and as a result of this metanoia, her child was healed. There is a promise that for those of us bold enough to really listen, to take into our deepest hearts the gospel message, there is a healing waiting for us too, and not coincidentally, a healing directed primarily at our children.

The Syro-phoenician woman’s faith converted Jesus, and saved the gospel from being small-minded. But it was Jesus’ willingness to be converted, to measure himself against the gospel, that was also necessary for conversion. I wonder if the gospel writer is hoping we’ll be converted as well.

I have to admit that I find it somewhat comforting that early on even Jesus still had room for improvement early on. I can more easily forgive my own sillinesses and faults. And it is encouraging to think that real change is possible. There are moments when God takes our hearts and prejudices and has to break them in order to transform us, to get us to see things newly. When we remember to love our enemies, and bless those who curse us, and give solace to those who would use us, to minister and reach out to those who target us, that is when the gospel lives in us.

And this afternoon and tomorrow, when we are bombarded with flag-waving, speeches and television exposes, when the news and remembrances and emails start circulating, meant to whip us up into a frenzy of patriotic fear and prejudice, especially then we need to remember who we are. We are no longer captive to the world’s notions of enemies and revenge. We have been set free. We live for something more. For us Christians it’s not the American Way – it’s the Jesus way, and it is narrow and difficult.

Like Jesus, we must be converted again and again. We must struggle to become Christian. But like Jesus, the Syro-phoenician woman and her daughter, there is the promise of transformation and redemption. There is understanding waiting for us in the bread. Eat in remembrance of him.